What is a stroke?

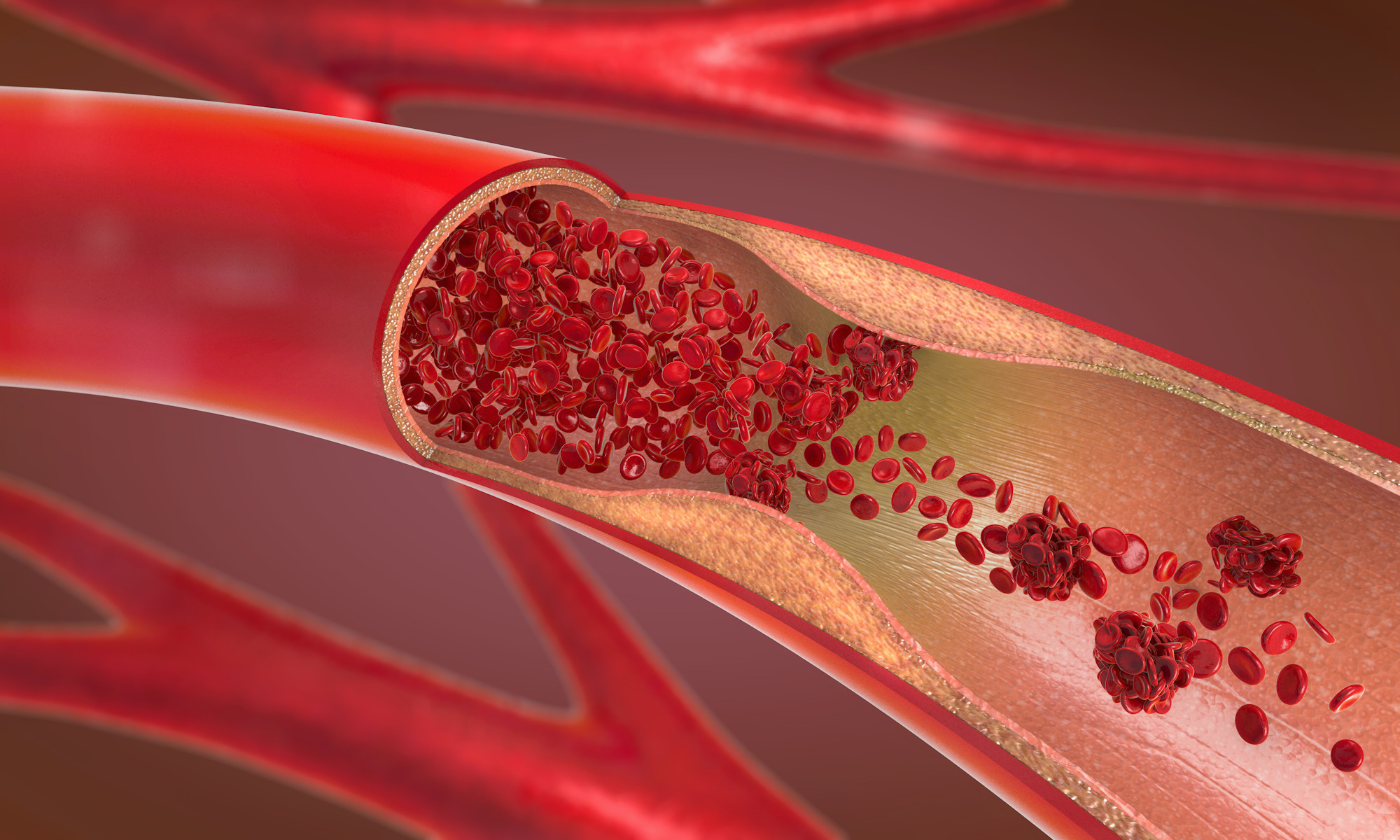

A stroke occurs when a part of the brain is damaged. This happens for two main reasons. Firstly, bleeding can occur into the brain and damage the brain tissue. This is called a haemorrhagic stroke. About 20% (1 in 5) of all strokes are haemorrhagic strokes. Secondly and more commonly, the arteries which take blood to the brain can become blocked. This called an ischaemic stroke. About 4 out of every 5 strokes are ischaemic strokes.

If a major artery to the brain is blocked, part of the brain tissue can die from lack of oxygen carried in the blood. When brain tissue dies the effects on the body will depend on what functions of the body that part of the brain controls. The effects on the body are commonly referred to as a stroke. For instance paralysis of the right side of the body (right sided stroke) will be due to damage to the left half of the brain. Inability to speak will also be due to damage to the left side of the brain in most patients, because it is the left side of the brain that controls speech. The severity of the stroke can vary enormously depending on how much of the brain is damaged.

| Face – SMILE (is one side droopy?) Arms – RAISE BOTH ARMS (is one side weak?) Speech – SPEAK A SIMPLE SENTENCE (slurred? unable to?) Time – Get to hospital FAST lost time could be lost brain |

Even if the main internal carotid artery blocks on one side of the neck the risk of stroke is only about 10-15% (1 in 10 to 1 in 7). This is because there is frequently enough blood reaching the brain from the opposite side and also from other arteries supplying the back of the brain (vertebral arteries). Each year about 7600 New Zealanders suffer a stroke. The FAST campaign (see left) aims to improve the recognition of stroke and its subsequent timely and rapid management. Although the FAST check does not mention leg symptoms they are of the same importance as weakness in the arms.

What is a TIA?

TIA stands for Transient Ischaemic Attack. This is sometimes known as a ministroke. A TIA is a stroke that lasts for less than 24 hours, and full recovery occurs.

Patients will experience the symptoms of a stroke, but then they will fully recover often within 2 or 3 hours. This is because the damage to the brain tissue is temporary and reversible. TIAs can affect the body in exactly the same way as a stroke, but in a TIA, the patient makes a complete recovery within 24 hours. Dizzines and giddiness, blurred vision and unsteadiness are not typical symptoms of a TIA or a stroke on their own. This important as these patients with these symptoms are unlikely to benefit from treatment of the carotid arteries in the neck.

| Clinical | Criterion | Score | |

| A | Age | >=60 years | 1 |

| B | Blood pressure | >=140/90 | 1 |

| C | Clinical features | Unilateral weakness | 2 |

| Speech disturbance only | 1 | ||

| D1 | Symptom duration | >=60mins | 2 |

| 10-59mins | 1 | ||

| <10mins | 0 | ||

| D2 | Diabetes | Present | 1 |

Why are TIAs important?

TIAs are important because they can be a warning that a more severe stroke may take place.

In some patients with TIAs there will be a narrowing in a major blood vessel to the brain. This blood vessel is called the internal carotid artery and there are two of them – one on each side of the neck. When this artery becomes diseased, it frequently becomes narrowed and lined by fragile material. This fragile material can break off into fragments and travel up to the brain and cause a stroke or TIA, by blocking the blood supply to an area of brain tissue. The fragments can be quite small and may only cause problems to a small area of brain. The area can be so small that the blood supply to other parts of the brain can compensate and a full recovery takes place. If a larger fragment breaks off or the main carotid artery blocks completely then a more severe stroke can occur.

Although all patients with a TIA should have further investigations, the chances of having a stroke after a TIA are greater if the patient is over 60 years old, has high blood pressure (>140 mmHg), temporary paralysis down one side and symptoms for more than one hour (Rothwell et al, 2005). The ABCD2 score shown in the table gives an approximate prediction of risk at 2 days following the first TIA based on the features shown. A score of 0-3 gives a risk of 1%, 4-5 a risk of 4% and a score of 6-7 a risk of 8% for further stroke in the next 2 days.

We now know that if a TIA occurs and the internal carotid artery is severely narrowed then an operation (carotid endarterectomy) to correct the narrowing can prevent further major and minor strokes. Special tests are needed to check the carotid arteries and see if they are narrowed.

| For individuals driving for domestic use: following a TIA or an episode of amaurosis fugax they should be warned not to drive for a period of at least one month following a single attack. Individuals with recurrent or frequent attacks should not drive until the condition has been satisfactorily controlled with no recurrence for at least 3 months (2.6.2). |

What is amaurosis?

Amaurosis or amaurosis fugax are terms used to describe a temporary loss of vision. Patients typically describe a curtain coming down or being drawn across their eye and part of their vision going totally black. It occurs only in one eye and may not affect the whole of the vision in that eye. It may only affect the outer half or upper half of the field of vision. The eyesight then improves and becomes normal over about 15-30 minutes as the black curtain is slowly pulled back.

Amaurosis is important because it is caused by a blockage in the blood vessels at the back of the eye. This blockage can occur in the same way as TIAs. In other words fragments break off from a narrowed artery in the neck, but instead of travelling to the brain they enter the blood vessel to the eye. This is purely a matter of chance and future fragments may go to the brain and cause a stroke and in fact patients with amaurosis are at increased risk of future stroke. For these patients also, an operation to correct a narrowing in the carotid artery in the neck can be beneficial. For these patients most benefit occurs in men over 75 years who have a history of previous TIA or strokes and with a narrowing over 80%.

How will I know if my internal carotid arteries are narrowed?

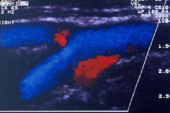

It is impossible to tell by a routine clinical examination if your carotid arteries are narrowed. Although abnormal sounds (bruits) can sometimes be heard over the arteries when listening with a stethoscope, this is a very poor indicator of narrowing of the arteries. About 4% (4 in 100) people over the age of 45 years will have a bruit. Only about 20% (1 in 5) of these patients will have a severe carotid narrowing (Aboyans, 2008). However, there is evidence that the presence of a carotid bruit may confer an increased risk of heart attack and cardiovascular death (Pickett, 2008). According to this study this risk of heart attack or cardiovascular death was about twice that of people without a carotid bruit (3.7 with bruit vs 1.9 without bruit per hundred patient years). Still the majority of patients will not suffer a serious event. The implication of the study is that an aggressive approach to treating vascular risk factors should be adopted but this is, as yet, not proven. The only way to know for certain if the carotid arteries are narrowed is to undergo an ultrasound scan of the arteries. This can be a very accurate test and will discover whether the arteries are normal or whether there is any narrowing present. Many surgeons will offer surgery on the basis of the scan test alone.

Should I arrange a scan of my carotid arteries?

You should definitely have a scan of the carotid arteries if you have had a TIA or have had a stroke from which you have made a full or partial recovery. This should be arranged urgently as the risk of further problems is greatest in the early period after the first event. It is important to remember that even in patients who have not made a full recovery from a stroke, surgery may be crucial in preventing further deterioration.

The figure right shows an ultrasound scan of normal carotid arteries at the point where the common carotid artery divides into the external and internal carotid arteries. If you have had no strokes or TIAs the need for a scan is more controversial as the risk of stroke is low (see below). However, if you have disease in arteries in other parts of the body such as the heart or the legs or you have high blood pressure and smoke cigarettes it may be worth considering a scan. In these circumstances there is an increased chance there will be narrowing in the arteries that has not yet caused symptoms. If you are under the age of 75 years you would be more likely to benefit from carotid surgery even if you have not yet had any TIAs or strokes. There is evidence that symptomatic elderly patients (more than 80 years old) are underinvestigated in routine practice (Fairhead JF, 2006). The incidence of symptomatic carotid disease increases with age and these patients are often willing to undergo surgery to reduce the risk of stroke. Age alone should not be a barrier to the investigation of reversible neurological events. These patients have at least as much to gain as younger patients. If you have had a very serious stroke which has left complete paralysis down one side of the body there is no need for a scan. In these circumstances no further deterioration can take place and so there is nothing to prevent by performing an operation.

What if the scan shows narrowing of the carotid arteries?

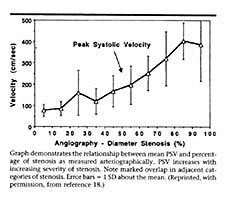

Traditionally, an angiogram is then performed to provide a road map of the blood vessels and to aid the surgeon further when planning surgery. All of the research that has shown benefit for surgery, was based on tests where an angiogram was performed. It is not completely certain that the same benefit would occur using a Duplex scan as the basis for surgery. There is some disagreement between the results of scanning and the results of angiography when assessing the narrowing in the artery. As shown in the graph below the velocity measurements made at ultrasound are not very specific for a given level of stenosis. An individual velocity measurement can correspond to a wide range of angiographic stenosis. The results of the scan test vary considerably between centres. This variation is influenced by a number of factors including the skill of the operator, different scanning techniques, different machines, training and the patients themselves (Jahromi et al, 2005).

Because angiography is an invasive test it is being replaced by other tests. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a test that is being used more frequently and has the advantage of not requiring any injections directly into an artery. MRA is non-invasive and low risk and can provide the surgeon with confirmation that the ultrasound measurements are in the right range. CT angiography is also a good test to confirm the ultrasound findings and the one that I currently use in my own practice to confirm narrowing identified on ultrasound scanning.

What is carotid endarterectomy?

Carotid endarterectomy is the operation used to remove the narrowing from the lining of the carotid artery. It may be performed under a general (patient asleep) or a local/regional (patient awake) anaesthetic. Both are used widely and there is no evidence that one is better than the other (see GALA trial). One of the first operations was reported in November 1954 from London (Eastcott HG et al, 1954).

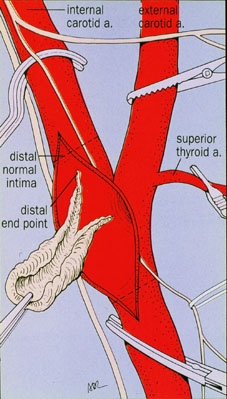

An incision is made in the neck from close to the ear lobe and courses down towards the collar bone in the midline. Some surgeons use an incision across the neck. Both incisions heal well. The arteries are located and prepared. During the operation to remove the diseased lining, the arteries must be clamped. This obstructs the blood flow to the brain and so surgeons frequently insert a plastic tube (shunt) to carry blood to the brain during this part of the operation. The diseased lining to the artery is carefully removed to leave as smooth a surface as possible. Many surgeons then close the artery using a patch to avoid causing further narrowing to the artery. A recent review has shown that closing the artery using a patch (patch angioplasty) lowers the risk of stroke or death not only around the time of the operation but also in the longer term (Bond R et al, 2004).

The diagram right is a representation of how a carotid endarterectomy is performed.

A drain is also usually left in place to remove any fluid that may accumulate in the tissues around the artery.

In my practice all operations are performed under general anaesthetic, a shunt is always used and I always use a patch to close the hole in the artery (Ali et al 2005). This reduces the risk of complications attached to surgery to a minimum. The picture left shows the material that can be removed from the artery during carotid endarterectomy. The browny-red areas are blood clot. A video below right shows the important stages in carotid endarterectomy.

What are the potential complications of carotid surgery?

The most important risk to patients is the risk of further stroke. Because the operation is performed on a diseased artery carrying blood to the brain, there is a risk during the operation or shortly after (particularly the first 24 hours), that a further stroke may occur. This is in fact uncommon and affects about 3% of patients or less. This means that in more than 95 patients out of every 100 no further stroke occurs around the time of the operation. However, it is important to realise that stroke is a real, but small risk of the operation. There is also a smaller risk of death, but this is very low at around 1% or less. This means that 99 out of every 100 people will not die.

There are a number of nerves that run close to the operation site that can be injured. The commonest is a sensory nerve (greater auricular nerve) to the upper part of the neck. Injury to this nerve can lead to some tingling or numbness in the neck and earlobe, but it is not usually a significant problem. The other nerve commonly seen is the hypoglossal nerve. This nerve controls movement of the tongue. It is occasionally injured and leads to deviation of the tongue to one side. Usually these problems are temporary because the nerve is bruised and not actually cut. There is a small risk of the artery renarrowing after surgery. This risk is low at probably less than 2% and rarely leads to symptoms.

What is the evidence that carotid endarterectomy is helpful?

Carotid endarterectomy is one of the most studied surgical operations. Three large trials, one in Europe (ECST) and two in North America (NASCET and VA Cooperative trial 309) examined patients who had suffered a TIA or a stroke. They clearly showed that in suitably selected patients, carotid endarterectomy reduces the risk of subsequent stroke. The information from these trials has been pooled to provide even more strong evidence that the operation is beneficial for patients with the appropriate level of narrowing (Carotid endarterectomy trialists’ collaboration).

What are the actual benefits from carotid endarterectomy?

The pooled data from the trials provides the firmest evidence of benefit. A total of 6092 patients with 35,000 years of follow up were analysed. Carotid endarterectomy was only helpful in patients with greater than 50% narrowing of the internal carotid artery. The more severe the narrowing the greater the benefit in reducing further strokes. There is no benefit in having an operation once the artery is blocked.

In patients with 50-69% narrowing the risks of stroke or death were reduced by 7-9% at 5 years after surgery. In patients with more severe narrowing greater than 70% the risks of stroke or death were reduced by 14-19% at 5 years after surgery. In certain groups of patients with very narrowed arteries the benefits of surgery can be even greater. The pooled analysis also showed that surgery within 2 weeks of a non-disabling stroke or TIA produced significantly more benefit than surgery at a later date. In a subgroup of patients with a 70% or greater narrowing, surgery within 2 weeks was associated with a 30.2% absolute reduction in the subsequent risk of stroke. It is important to realise that these reductions in risk for a patient are very great when compared with other medical measures to prevent stroke or death. For instance the use of drugs to lower the cholesterol level only reduces the risk of death by 1-2%. The benefits for carotid endarterectomy are many times greater than taking tablets. Be careful when reading claims regarding reductions in risk particularly for medications used to lower blood pressure and cholesterol.

For instance a reduction in the risk of dying from 2% (2 in 100) to 1% (1 in 100) is only an absolute benefit of 1%. That is only 1 person in every 100 will be helped. Ninety nine patients in every 100 will take tablets with no benefit. Unfortunately, to make this 1% absolute benefit appear greater, it is sometimes expressed as a 50% relative risk reduction because the risk has been halved from 2% to 1%. There is still true benefit in these circumstances, but it is much less than it first appears. The old saying that there are lies, damn lies and statistics is nearly true.

What if I have a narrowed artery but no symptoms?

The situation for these patients has changed dramatically with the publication of the ACST trial. The ACST trial has clarified the true benefits of surgery for asymptomatic carotid artery disease. There is definite benefit, although small, in selected patients.

Newer developments

Carotid endarterectomy has a clear benefit proven in rigorous trials in patients with symptomatic narrowing of the carotid artery. However, it requires an operation and a general anaesthetic, although some surgeons do perform this procedure under local anaesthetic.

Some centres are performing carotid angioplasty. This is a procedure to stretch the artery using balloons with or without the addition of metal stents. This is not universally available and not suitable for all patients, but is an area which is rapidly developing. It is important that the results of this new procedure are compared with surgery which in most patients is already a very safe operation. One potential problem with carotid angioplasty is that while the balloon is being inflated in the carotid artery fragments from the lining of the artery may break off and travel to the brain and cause a stroke. This problem is prevented by using various types of protection devices. These are basically strainers or sieves which filter the artery just beyond the balloon and prevent tiny pieces travelling to the brain as they are caught in the strainer. There has been an increase in the use of this procedure in the USA, but mortality rate has been reported at 4 times greater and stroke rates nearly twice that of conventional surgery (Nowygrod, 2006). A French study has reported high rates of stroke or death after carotid angioplasty and stenting when compared with surgical endarterectomy (9.6% stenting versus 3.9% for surgery. The SPACE Collaborative Group were unable to prove, in a larger trial, that angioplasty and stenting were equivalent. The CREST (carotid revascularisation endarterectomy versus stenting trial) study has recently reported results at the American Stroke Association 2010 meeting. This was a multicentre US study over 9 years in recently symptomatic patients. At 30 days the rate of stroke was significantly higher with stenting at 4.1% versus 2.3% with surgery. Heart attacks were more common in the surgical group at 2.3% versus 1% with stenting. The overall stroke and death rate was twice as high in the stenting group when compared with the surgical group. A recent meta-analysis has similarly reported that surgery has lower short term risks when compared with angioplasty and stenting. At later time intervals after full recovery from the initial intervention risks seem to be fairly even between surgery and stenting but as the short term risk is greater with stenting it remains a more risky intervention than surgery.

Carotid surgery is still the gold standard. It has a proven track record of reducing the risk of stroke in the longer term. For the vast majority of patients the operation will be uneventful and they will only be in hospital for 2-3 days. Angioplasty has not been proven as a safer alternative or even equivalent in the short term. There is no real reason that it should continue to be performed except in special circumstances where surgery may be particularly difficult and carry significantly increased risk.

Useful links

http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/carotidendarterectomy/Pages/introduction.aspx

http://www.vasculardoc.net/content/carotid.html – Personal site of an American vascular surgeon. Information on all types of vascular conditions.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ImHe-7RoqVc – youtube videos of carotid surgery

http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/stroke/carotid_endarterectomy_backgrounder.htm www.stroke.org – Site of National Stroke Association

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/tutorials/carotidendarterectomy/htm/index.htm

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/databases/alerts/stenosis.html

http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com http://www.nlm.nih.gov/databases/alerts/carotid.html

http://www.vascularweb.org/vascularhealth/Pages/carotid-endarterectomy.aspx

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BlCaeJ0-LRg http://c561949.r49.cf2.rackcdn.com/videos/SVS_Perler_RiskBenCE.wmv

Carotid stenting

http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/carotidendarterectomy/pages/alternatives.aspx

http://c561949.r49.cf2.rackcdn.com/videos/SVS_Zhou_CrtdStent_Final.wmv http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=ip_08

References

Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossman E et al. A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2005: 366: 29-36.

Aboyans V, Lacroix P. Carotid bruit: good for silent cardiovascular disease? Lancet 2008; 371: 1554-56.

Pickett CA, Jackson JL, Hemann BA, Atwood JE. Carotid bruits as a prognostic indicator of cardiovascular disease and myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2008; 371: 1587-1594.

Fairhead JF, Rothwell PM. Underinvestigation and undertreatment of carotid disease in elderly patients with transient ischaemic attack and stroke: comparative population based study. Brit Med J 2006; 333: 525-7.

Jahromi AS, Cina CS, Liu Y, Clase CM. Sensitivity and specificity of color duplex ultrasound measurement in the estimation of internal carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg 2005; 41: 962-72.

Eastcott HHG, Pickering GW, Rob CG. Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet 1954; 2: 994-996.

Bond R, Rerkasem K, Naylor AR, AbuRahma AF, Rothwell PM. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of patch angioplasty versus primary closure and different types of patch materials during carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40: 1126-35.

Ali T, Sabharwal T, Dourado RA, Padayachee TS, Hunt T, Burnand KG. Sequential cohort study of Dacron patch closure following carotid endarterectomy. Brit J Surg 2005; 92: 316-321.

European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 1998; 351: 1379-87.

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaborative Group. The final results of the NASCET trial. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1415-25.

Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA et al for the Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaboration. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 2003; 361: 107-16.

Nowygrod R, Egorova N, Greco G et al. Trends, complications, and mortality in peripheral vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg 2006; 43: 205-216.

Mas J-L, Chatellier G, Beyssen B et al. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1660-71.

The SPACE Collaborative Group. 30 day results from the SPACE trial of stent-protected angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2006; 368: 1239-47.

Meier P, Knapp G, Tamhane U, Chaturvedi S, Gurm HS. Short term and intermediate term comparison of endarterectomy versus stenting for carotid artery stenosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Brit Med J 2010; 340: c467.