What is kidney failure?

The kidneys work as a filter to remove waste products that build up normally in the blood stream. These waste products are then passed from the kidneys to the bladder by two tubes (ureters) running from the kidneys to the bladder. The waste products are dissolved in water and stored in the bladder as urine. Kidney failure occurs when the kidneys are unable to remove waste products from the blood stream and they build up in the blood stream (uraemia). Early on this may not be a problem, as the kidneys may continue to do some filtering work and are able to compensate for a mild degree of failure. The kidneys are able to compensate even when one of them is removed, but eventually they are unable to keep pace with the build up of waste products (chronic renal failure). If treatment is not started the patient with kidney failure will die. In these patients there is usually time to permit full discussion and planning of treatment as the kidney failure develops slowly. Sometimes kidney failure can develop more suddenly (acute renal failure). In these circumstances there is little time to plan treatment, which must be started immediately. This may happen as an isolated problem or as part of a serious acute illness.

What treatment is available for kidney failure?

The treatment for kidney failure is dialysis. Dialysis is a way of removing the waste products from the blood stream when the kidneys cannot cope. It is like having an artificial kidney.

There are two main methods of dialysis: HAEMODIALYSIS or PERITONEAL DIALYSIS (CAPD). Peritoneal dialysis involves placing a plastic tube into the abdomen and running special fluids in and out of the abdomen. The waste products dissolve in the fluid and are removed when the fluid is removed from the abdomen. Haemodialysis is a method that requires access to the blood stream. In other words a connection between the blood stream and the artificial kidney (dialysis machine) is needed to enable this method to work. There are many ways of making this connection to the blood stream:

Arteriovenous shunts – these are plastic tubes with one end inserted into an artery and the other end into a vein. When the patient requires dialysis the tube is connected to the dialysis machine. Shunts are rarely used these days.

Central Venous Access– this is where a hollow tube (central line) usually with 2 ports is placed into a main vein. They are usually placed in a main vein in the neck, but are also sometimes placed in veins in the leg. When dialysis is required the tube is connected to the dialysis machine. These tubes are in common use and are especially important fro a patient who requires dialysis in an emergency. Because there is a permanent connection from the blood stream to the outside there is a risk of blood stream infections developing (septicaemia).

Creation of a fistula – a direct connection between an artery and a vein is created at a surgical operation. This new connection is called a fistula. The vein enlarges over a period of weeks because arterial blood at a higher pressure is now flowing through the vein. When dialysis is required needles are inserted into the vein and connected to a dialysis machine. Planning for the creation of a fistula should take place before dialysis is required. Patients who have a fistula in place ready for dialysis, when required, have a better chance of surviving their renal failure than patients who have no fistula.

How do fistulae work?

All fistulae share a common theme. The theme is the creation of a connection between a high flow, high pressure artery and a low flow, low pressure vein. This diverts blood from the artery into the vein increasing the blood flow and the pressure in the vein.

Over time the veins expand and the vein walls become much thicker (vein maturation). The time taken for the vein to mature can vary depending on which type of fistula is created. Wrist (radiocephalic fistulas) take approximately 4-6 weeks. Brachio-basilic (upper arm) fistulae take longer, approximately 8 weeks, to mature. When the vein matures it is much easier to insert needles into the veins, as the veins are larger. The veins can also withstand repeated needle punctures over many years.

What are the different types of fistula?

There are many different types of fistula that have been devised to help patients to dialyse. Fistulae are performed in 2 major parts of the body – in the arms or in the legs. Arteriovenous fistulae created in the arm are by far the commonest type of fistula used for dialysis.

Any fistula, whether it be in the arm or the leg, can be formed in 2 ways. Firstly, the surgeon may use the native arteries and veins found in different parts of the body and, using various surgical techniques, join a vein to an artery. These are called autogenous fistulae and are always the first choice because they are likely to work for longer and need less maintenance to keep them going.

The alternative technique uses an artificial material (usually goretex (PTFE)) as a bridge between an artery and a vein. This type of operation is commonly performed at the elbow with the loop of artificial material placed in the forearm. As the artificial material used is PTFE (Goretex) and the operation is referred to as a PTFE forearm loop. In patients who have artificial material implanted, dialysis needles can be placed directly through the material to enable dialysis to take place. This can be a very successful technique, but in general these fistulae do not last as long as autogenous fistulae and need more maintenance procedures to keep them functioning. For the surgeon it is not usually a matter of choice. Artificial materials should only be used when there is no obvious autogenous fistula that can be created or the chances of success are clearly worse than trying to use an artificial graft.

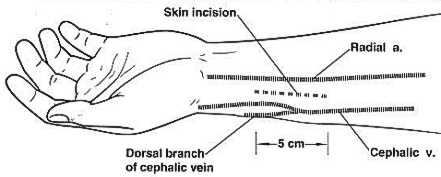

Radiocephalic wrist fistula (Brescia-Cimino fistula): This is the most common fistula and is created at the wrist (primary radiocephalic fistula). A small vein (cephalic vein) and a small artery (radial artery) are joined together using very fine stitches (see below). This fistula was first devised in the mid 1960s and is still the most common fistula in use for haemodialysis.

It is possible to create this sort of fistula in any part of the lower half of the forearm. Above this level the muscles of the forearm become too bulky and it is better to use blood vessels around the elbow. A particular type of wrist fistula can be created in some patients at the base of the thumb (snuffbox fistula). It is also possible to use segments of vein in the upper forearm and create cephalic or basilic loops in the forearm but with connections to the brachial artery at the elbow.

Brachio-cephalic fistula: a brachio-cephalic fistula is formed at the front of the elbow by connecting the cephalic vein and the brachial artery at the elbow. The cephalic vein is found towards the outside of the upper arm and as it enlarges this vein can be used for dialysis.

Brachio-basilic fistula: a brachio-basilic fistula is formed at the elbow by connecting the basilic vein and the brachial artery at the elbow. The basilic vein is found on the inside of the upper arm but it is also quite deeply placed and so it needs to be transposed (moved) to a more superficial position. This involves extra incisions along the inside of the upper arm and the graft is then tunnelled in the subcutaneous tissues to enable easier access. Once a brachio-basilic fistula has been formed it is more difficult to form a brachio-cephalic fistula and so surgeons will usually attempt to create a brachio-cephalic fistula first if possible. Fortunately, if the brachio-cephalic fistula fails it is still possible to create a brachio-basilic fistula.

PTFE loops: sometimes it is not possible to create fistulae using autogenous vein. In these cases an artificial plastic tube is attached to the brachial artery at the elbow and tunnelled as a U-shaped loop in the forearm. It is then joined to a vein at the elbow and the tube itself can be used for dialysis – a PTFE loop graft. PTFE may also be placed in the upper arm as a graft between the brachial artery and the axillary vein in the armpit.

Leg loops: If it is not possible to create a fistula in either arm then it may be possible to form either a vein loop or a PTFE loop in the thigh.

There are many other types of fistulae available to surgeons but they are required much less frequently than those listed above. The more unusual variations although not routinely required can be very useful in patients who have already had multiple operations to provide vascular access.

Which type of fistula is the best?

It has become clear that the best type of fistula to have created should use the native veins and arteries. Although artificial grafts can be used successfully they are usually not as useful for as long and require far more procedures, such as angioplasty, to keep them patent and useful for dialysis.

It is best to create a fistula as close to the hand as possible so that a long length of vein on the forearm and arm is available for dialysis. It is usually preferable to use the non-dominant hand (use the left wrist if the patient is right handed). It is sometimes suggested that elderly patients are not as suitable for primary fistulae because their blood vessels may be more damaged and patency rates are not as good. This is not true. Elderly patients can benefit just as much as younger patients from primary fistulae. In patients with diabetes, wrist fistulae are much more likely to fail early but are still worth considering as a first option.

How will I be assessed before surgery?

History: The surgeon will need information about previous vein punctures (such as from taking blood or IV drips), central lines (tubes placed in large veins in the neck) and arterial lines (tubes placed usually in the radial artery at the wrist). General health information and medication will be important especially if the patient is taking warfarin which can cause bleeding.Examination: The arms of the patient should be examined with and without a tourniquet looking for veins that may be suitable for fistulae. Scars from previous central lines, intravenous lines and arterial lines are also important. The arterial pulses in the arms should be checked.

Investigations: Sometimes a history and examination will be enough for the surgeon to decide on which operation is required. This is often the case when patients are undergoing fistula formation for the first time. There is an increasing use of imaging to help in planning the optimum surgery. Venography (outlining the veins), Duplex (looking at flow in veins and arteries) and arteriography (outlining arteries) are being used more and more frequently.

How are fistula operations performed?

All of the operations to create a fistula require some sort of anaesthetic. Commonly, a local anaesthetic is used for a fistula at the wrist. This requires the injection of an anaesthetic under the skin which then numbs or freezes the area where the operation will be performed.

Other types of fistulae may be performed under local anaesthetic, but are also performed under regional or general anaesthesia. In regional anaesthesia the nerves supplying a whole region may be anaesthetised, but the patient remains awake. For instance it may be necessary to “freeze” the nerves to the whole arm so an operation can be performed, but the patient will be conscious throughout. A general anaesthetic means that the patient will be asleep throughout the operation. The choice of anaesthetic may be made after discussion between the surgeon, anaesthetist and patient and will also depend on which type of operation is being performed. The operations are commonly performed by surgeons using some form of magnification. This is because the blood vessels are often very small and the stitching needs to be very exact. Most operations will not take longer than 90 minutes.

How will I know if my fistula is working?

After the artery and vein have been joined together there will be a much faster blood flow in the vein. Because the join is an artificial connection, the flow is not as smooth as in normal blood vessels. Turbulence is created in the blood, much as it occurs in river water passing over rocks and boulders. This turbulence can be felt through the skin of the arm over the vein as a buzzing sensation (medically termed “a thrill”). This turbulence also creates a noise (bruit) that can be heard with a stethoscope. If a thrill or buzz is present, your fistula is working. If it is not present your fistula may have stopped and medical help should be sought immediately.

How long will a fistula last?

How long a fistula lasts depends upon what type of operation is performed and the condition of the artery and vein before surgery. One year after surgery to create a fistula at the wrist (radiocephalic fistula) approximately 70-80% of patients will have a functioning fistula that they can use for dialysis.

Can I prolong the life of my fistula?

There are no fool proof ways of ensuring that your fistula continues to work well. Varying the needle insertion sites for dialysis may be helpful and a combination of aspirin and diyridamole to thin the blood has a small benefit (Dixon BS et al, 2009). Patients who receive dypridamole plus aspirin have an absolute risk reduction of about 5% in the rate of losing graft patency. This only translates into a prolongation of graft survival without other procedures of 6 weeks (Lok, 2009). It is important not to smoke. Loose clothing on the arms will prevent constriction of the veins. Avoid working with the arm up (eg painting a ceiling) as this can lead to compression of major veins around the shoulder and lead to thrombosis (blockage of the vein by blood clot).

If you notice any changes in the fistula they should be reported to your doctor. Changes which may be important are the buzz becoming fainter, the buzz disappearing and the fistula becoming softer. Problems with flows on dialysis or increased return pressures are also important but there appears to be no benefit for routinely monitoring flow as a screening tool for potential graft/fistula flows.

What are the possible complications from fistulae?

The fistula may block

Although most patients will leave the operating theatre with a functioning fistula and a palpable “buzz”, the main problem they are likely to run into later is that the fistula will block. The easy way to tell if a fistula has blocked is to feel the fistula. If the buzz or thrill has disappeared then it has probably blocked. If you think this has happened it is important to see a doctor immediately. Sometimes further surgery can save the fistula and keep it running, but it is often better to construct a new fistula.

Failure to mature

Sometimes the fistula may continue to work, but the vein may not enlarge sufficiently to permit its use for dialysis (failure to mature). It is not always clear why this occurs, but it usually means a new fistula will have to be created.

Vascular steal

Because blood from the artery is being diverted into a vein before it reaches the hand some patients can develop problems from shortage of blood to the hand (steal syndrome). This does not occur in most patients, but can be a serious problem if it does arise. It is very uncommon in patients who have fistulae at the wrist. It is more likely to arise when fistulae are created in bigger blood vessels aound the elbow, when it may occur in up to 10% of patients.

Symptoms of steal can include a cold hand, pain, discolouration and ulceration. Symptoms are typically worse on dialysis. Steal may be more likely to develop if the patients has peripheral vascular disease and/or diabetes. Before treating the steal it is important to fully investigate the cause with a fistulogram and/or an ultrasound. On some occasions an arterial narrowing proximal to the fistula can be responsible and it often easily treated with angioplasty.

If steal syndrome develops the fistula may have to be tied off to restore blood flow to the hand. This will solve the steal but the fistula will then be lost. Sometimes other procedures are available to improve blood flow and at the same time to preserve the fistula. These procedures include banding, interposition grafting and the DRIL (distal revascularisation and interval ligation) procedure. Interposition grafting with a tapered synthetic graft can be effective and has the advantages that normal arteries are left intact. It is essentially a more controlled form of banding.

Vein narrowing

In some patients narrow portions (stenosis) can develop in the vein. These may cause reduced flow in the fistula or high return pressures when the patient is on dialysis. The fistula thrill may reduce and the fstula may become noticeably softer. When this happens further investigations are required such as Duplex scans or a fistulogram. A fistulogram involves placing a needle into the vein and injecting a dye to obtain an outline of the fistula when an X-ray is taken. Narrow sections of a fistula can either be treated by angioplasty, stenting or surgery to open up the narrowing.

Treating a venous outflow narrowing appears to be best performed with a stent-graft rather than just simple angioplasty (Haskal et al, 2010). When stent-graft was used in place of simple angioplasty patency rates were doubled at 6 months (51% of grafts still patent with stent-graft vs 23% patent with angioplasty alone at 6 months). Longer term outcomes will be important to monitor.

Other complications

Small and even large aneurysms can develop in the veins. These sometimes require treatment but are often left alone unless they become very large.

Synthetic grafts can develop infection from multiple punctures and this can be a serious problem which requires removal of the graft and loss of the fistula.

Useful links on vascular access surgery and peritoneal dialysis

http://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/leadership-ministry/clinical-groups/national-renal-advisory-board/papers-and-reports – Detailed reports and information on renal dialysis services in New Zealand

http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_updates/doqi_uptoc.html#va – From the National Kidney Foundation (USA). Recent study and review of dialysis outcomes quality initiative (DOQI). Large amounts of information on all aspects of dialysis and and vascular access with protocols and recommended pathways of management. Very informative site but quite technical.

http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/vascularaccess/

http://www.emedicine.com/ped/topic3050.htm

http://www.vascularweb.org/vascularhealth/Pages/dialysis-access.aspx

Peritoneal dialysis

www.ispd.org/guidelines/articles/gokal/page01.php3

www.laparoscopy.net/access/pdc.htm

http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines.cfmwww.ispd.org

www.renalweb.com/topics/out_pdadequacy/pdadequacy.htm

http://www.kidney.org/ – Lots of information about all aspects of kidney failure.

References

Burt CG, Little JA, Mosquera DA. The effect of age on radiocephalic fistula patency. J Vasc Access 2001; 2: 60-63.

Dixon BS, Beck GJ, Vazquez MA et al. Effect of dipyridamole plus aspirin on hemodialysis-graft patency. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2191-201.

Lok CE. Antiplatelet therapy and vascular access patency. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2240-2242.

Haskal ZJ, Trerotola S, Dolmatch B et al. Stent graft versus balloon angioplasty for failing dialysis-access grafts. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 494-503.