What is peripheral vascular disease(PVD)?

PVD is widely used to refer to hardening of the arteries in the legs. In some contexts it can be used to refer to any sort of occlusive vascular disease anywhere in the body, except the heart. Intermittent claudication is caused by peripheral vascular disease.

What problems can PVD cause in the legs?

PVD can cause a variety of problems in the legs ranging from no symptoms at all, to amputation of the leg. The mildest forms of arterial disease frequently do not produce any symptoms at all. As the disease becomes worse, it leads to cramping pain in the muscles of the leg on walking (intermittent claudication). If the disease becomes very severe, more serious problems can develop. The most worrying symptoms are a continuous pain (rest pain) in the foot especially at night, black toes (gangrene) and ulceration. When these problems develop the patients are sometimes described as having critical limb ischaemia. This means that the patient has developed problems that are putting the leg at risk of amputation. Many patients with and without PVD can experience night cramps in the legs. Although these cramps can be quite severe, they are not caused by hardening of the arteries and are not a risk to the legs.

What is Intermittent Claudication?

Claudication is a term derived from the Latin word meaning “to limp”. Intermittent claudication (vascular claudication) describes the pain that develops in the muscles of the legs when taking exercise, such as walking. Commonly, the calf muscles are the most affected, and patients describe a cramping discomfort, as characteristic of the pain. Initially patients may be able to walk through the pain, but as the disease progresses further, this is not possible and the claudication pain causes limping and can only relieved by resting. Most patients find that their claudication symptoms are worse on walking uphill. They can also be worse when walking barefoot or wearing flat shoes. Any situation in which the muscles of the legs have to work harder will worsen claudication symptoms. Some patients develop symptoms in their thighs and buttocks and PVD may also lead to impotence in men (Leriche syndrome). The development of particular claudication symptoms, depends on exactly which arteries are affected.The symptoms are intermittent because they resolve when resting. The symptoms of claudication can be mimicked by many other conditions which cause pain in the legs such as arthritis and nerve problems (neuropathy). Neurogenic claudication is pain in the legs due to compression of nerves in the spinal cord and can be very difficult to distinguish from claudication due to arterial problems.

How common is intermittent claudication?

The Edinburgh Artery study (Leng GC et al 1995) examined this question. About 4 out of every 100 (4%) people over the age of 55 years experienced symptoms, but there was evidence of hardening of the arteries in a further 25% of patients who were not experiencing symptoms. In general PVD is commoner in men.

Why does PVD cause pain in the legs?

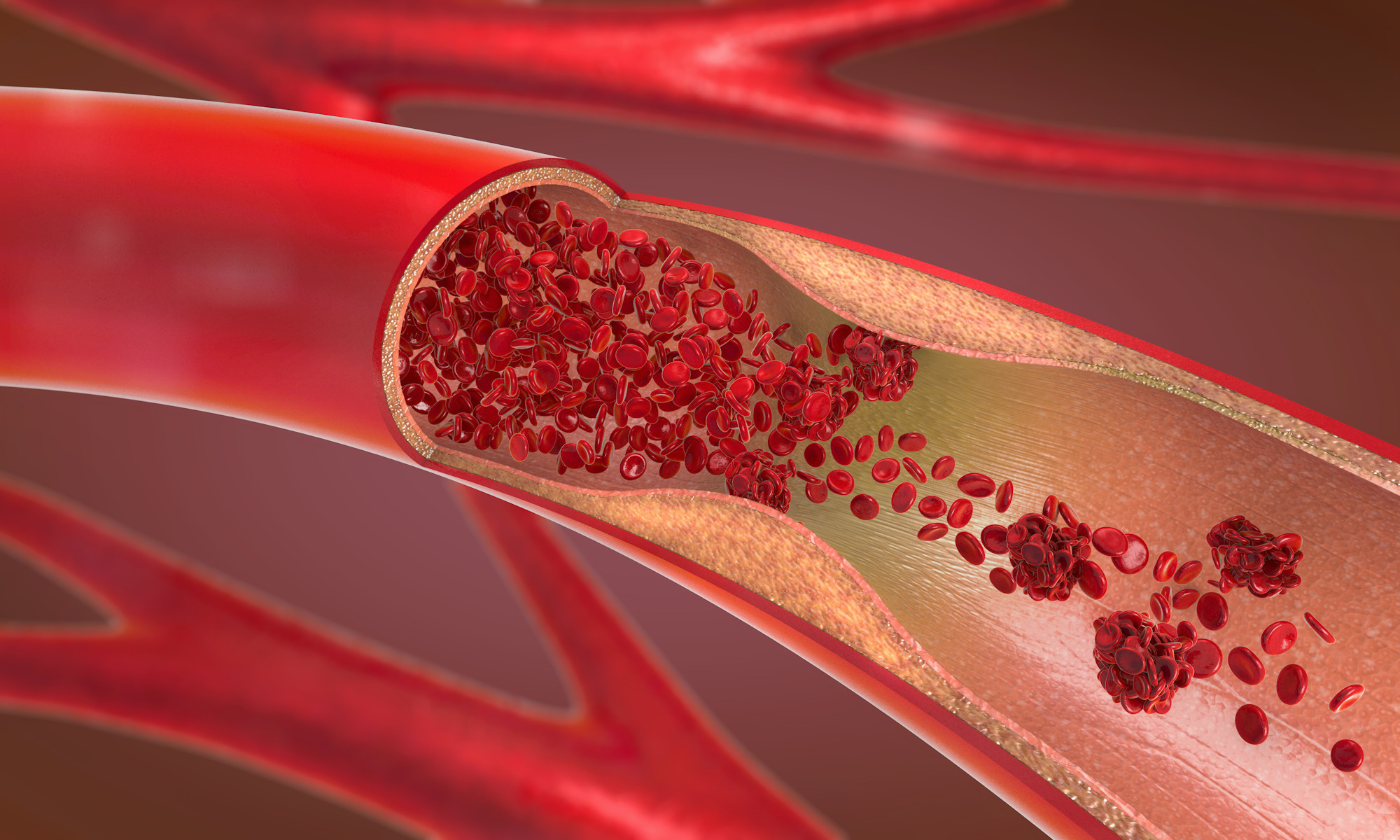

Pain develops because there is a narrowing or blockage in the main artery taking blood to the leg due to hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis). Over the years cholesterol and calcium build up inside the arteries. This occurs much earlier in people who smoke and those who have diabetes or high levels of cholesterol in the blood. The blockage in the arteries means that the blood flow is reduced. At rest there is enough oxygen in the blood reaching the muscles to prevent any symptoms. When walking the calf muscles need more oxygen, but because the blood flow is restricted the muscles cannot obtain enough oxygen from the blood and cramp occurs. This is made better by resting for a few minutes. If greater demands are made on the muscles, such as walking uphill, the pain comes on more quickly. Many patients also notice that if they are carrying heavy bags the pain comes on sooner because the leg muscles are having to work harder. Walking in bare feet or very flat shoes also tends to make the symptoms worse. Intermittent claudication is a manifestation of chronic (longstanding) peripheral vascular disease which has usually taken many years to develop. In some patients the blood flow to the legs can be so restricted that there is barely sufficient oxygen reaching the tissues even while resting. In these patients severe pain can develop particularly at night and it is only eased when the leg is dangled down over the edge of the bed. When this happens and tests show reduced blood flow, then critical limb ischaemia has developed and the leg is at risk of amputation.

What are the signs of PVD in the legs?

In longstanding PVD (the usual case for patients with intermittent claudication) the tissues have frequently adapted to the shortage of blood and consequently there may be little to see to indicate PVD. On feeling the leg it may be a little cooler and some of the pulses in the leg may be absent. In more severe cases the foot may be quite blue and dusky. The foot may become very pale when lifted up above the heart with the patient lying down and become a bright red when placed dependent (Buerger’s sign, sometimes called sunset foot). The shortage of blood can cause the development of ulcers or gangrene. In the less common situation when patients develop a very sudden (acute) shortage of blood to the leg and foot the limb may turn white (pallor), the pulses will be absent (pulseless), the limb will be cold (poikilothermia), painful, parasthetic (numb or tingling) and may be paralysed. The most important features in a limb with an acute shortage of blood are the numbness and paralysis as these indicate a very severe ischaemia with impending limb loss. Doppler studies may be helpful in both the chronic and acute situations by confirming the diagnosis but are not critical in deciding further management.

Does the blockage in the artery ever re-open?

The blockages in the arteries never re-open spontaneously. Fortunately, the blockages themselves are not dangerous. It is only the symptoms they cause that are important. Many people live for many years with blockages in the arteries that never cause any serious problems.

Will intermittent claudication get worse?

Often when patients develop claudication their symptoms can be worse in the first few months. This is because it takes time for the body to adjust to the restricted blood flow. After 2-3 months the situation can improve due to smaller arteries opening up (collateral circulation) and carrying more blood around any blockages. Smaller blood vessels, although not the major blood vessels to the leg, usually carry enough blood to prevent severe disability. Overall about one third of patients with claudication will improve, one third will remain stable and one third will deteriorate. In the majority of patients (>65%) the symptoms will remain stable or improve. The patients whose symptoms deteriorate tend to be those who continue to smoke. Further improvements in walking can be made by taking regular walks. This appears to develop fitness in the affected muscles (much as in an athlete). A formal exercise programme can be a very effective way of improving walking distance. Unless the leg is at risk, it is important not to attempt to improve the blood supply at this early stage in the disease as many patients will develop spontaneous improvement without any help.

What is the risk of losing my leg?

Very few patients with intermittent claudication end up with an amputation and your surgeon will make every effort to avoid amputation, if your leg is at risk. Estimations of the risk of amputation vary, but it probably affects less than 5% (5 in 100) of patients with claudication. This means that 95 patients out of every 100 will not lose their leg. Two epidemiological (population) studies indicated a risk of major amputation of less than 2% for patients who developed claudication (Kannel WB et al 1985, Widmer LK et al 1964). Most patients will develop obvious signs that the vascular disease is deteriorating before an amputation becomes necessary and this will provide time so that improvements can be made in the blood supply to the affected leg and so avoid amputation.

The most important things you can do to reduce your risk of severe problems in the legs are to keep walking, lose weight and stop smoking!

Although the risk of losing a limb is low, hardening of the arteries in the legs is a marker for generalised atherosclerosis. PVD is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular death and 50% of patients with claudication may die within 10 years from the effects of hardening of the arteries in other parts of the body (Shearman CP, 2002). This is why it is so important to stop smoking and treat other vascular risk factors.

How can I help my intermittent claudication?

There are several things you can do which may help. The most important are to stop smoking, take regular exercise, lose weight and to have any vascular risk factors treated (Davies AH 2000, Burns et al 2003). This can not only improve your walking and reduce the low risk of limb loss even further, it can also help to reduce problems from generalised atherosclerosis. Vascular risk factors are factors which put a patient at increased risk of hardening of the arteries.

Smoking – If you are a smoker you must make a determined effort to give up completely. Tobacco is harmful on two counts. Firstly, it speeds up the hardening of the arteries, which is the basic cause of the trouble and secondly, cigarette smoke constricts the small collateral vessels and reduces the amount of blood and oxygen to the muscles. The best way to give up is to choose a day when you are going to stop completely rather than trying to cut down gradually. If you do have trouble giving up please ask your doctor who can give you advice on nicotine gum and patches or put you in touch with a support group. If you ever need to have angioplasty or surgery the results are likely to be much poorer if you are still a smoker.

Cholesterol and Diet – It is very important not to put on weight, because the more weight the leg muscles have to carry around the more oxygen and hence blood flow they will need. Your doctor or dietician will give you advice with regard to a weight reducing diet. If your blood cholesterol is high you will need a low fat diet and may also require cholesterol lowering drugs.

Exercise – There is good evidence that patients with intermittent claudication who take regular exercise can increase their walking distance (the distance that they can walk before they have to stop because of pain in the muscles). To develop improvements in walking distance it is important to set aside time to exercise. Walk at an easy pace until the pain comes on and then try to push on a little further. When the pain increases to near maximum, stop and rest until the pain disappears, then return to where you started. Remember the distance that you walked on this first occasion and walk the same distance the next day. Repeat the same exercise distance for one week and on the second week increase the distance slightly. This increased distance is then used for the second week and on the third week the distance is increased slightly further. It is important to only increase the distance walked each week by a small amount otherwise it will become too difficult. It is important to exercise at least 3-4 times each week and very gradually over a period of weeks to increase the walking distance. Initially this can be uncomfortable but you should start to feel real benefit at about 6-8 weeks. It is important not to try and increase your walking distance too rapidly as this can become painful and frustrating.

Supervised exercise programmes are available in some centres. They have shown the most benefits when the exercise session lasted more than 30 minutes, when sessions took place at least 3 times each week, when the patient walked until near maximal pain was reached and when the programme lasted at least 6 months (Stewart et al, 2002). Exercise can improve walking ability in patients with intermittent claudication by 150 per cent (Watson et al, 2008). Improvements in walking from an exercise programme appear to be better than any medication including cilostazol (see below) and may be equivalent in the long term to walking improvement from angioplasty. Angioplasty can bring faster improvements to walking ability, but these may not last. Angioplasty also has a number of intrinsic risks. A recent study comparing supervised exercise and angioplasty demonstrated good improvements in up to 50% of patients with exercise alone and at the end of one year there were no major differences between patients undergoing angioplasty and those managing with exercise. Interestingly nearly 70% of patients in the angioplasty groups developed renarrowing of the treated artery by one year (Mazari et al, 2012).

Flat shoes. Some patients find that flat shoes can make their symptoms worse. A raised heel to the shoe will raise the heel of the foot and reduces the work that the calf muscles have to perform. This can increase your walking distance.

Blood pressure – It is important that your blood pressure is measured, and if found to be consistently high it should be treated by your doctor. Raised blood pressure can cause further deterioration in hardening of the arteries if left untreated.

Diabetes – If you have diabetes it is important that your sugar levels are tightly controlled as this helps to reduce the risk of future problems.

Thrombophilias. Sometimes specific treatment for thombophilias can be helpful.

Are there any tablets I can take?

There is no medicine that will unblock the arteries. Claims are made for some tablets that dilate the blood vessels but there is little evidence that they make a significant difference, enough to improve the quality of life. Cilostazol is a tablet that is not available in New Zealand, but does appear to improve walking distance. It is best taken at a dose of 100mgs twice daily and produces about 20% improvements in maximal walking distance (Strandness DE et al 2002). Cilostazol can cause headache, diarrhoea and palpitations. Naftidrofuryl is another drug that has shown some small benefits by increasing the maximum walking distance by approximately 50-60 metres, but here also it is doubtful whether this makes a significant difference to quality of life.

A low dose of Aspirin (75milligrammes) is advised for patients with PVD. This is because it makes the blood less sticky and reduces the chances of having further problems in any artery in the body, not only the legs. Aspirin may occasionally cause irritation of the stomach and so if symptoms of indigestion or heartburn develop it should be stopped. Aspirin produces a 20% relative reduction in the risk of heart attack, stroke or death due to vascular disease, in patients with PVD. The absolute benefit is smaller (8.1% reducing to 6.5%, that is 98 out of 100 patients who take aspirin do not have any benefit). Combinations of aspirin-like drugs may also be better than aspirin alone (Robless P etal, 2001). Clopidogrel is a newer, more expensive, alternative to aspirin which may be used in some patients intolerant of aspirin. It is more expensive than aspirin, but a recent large randomised clinical trial comparing aspirin with clopidogrel did find a very small benefit in favour of clopidogrel in terms of reduction of cardiovascular events (CAPRIE Steering Committee, 1996). Chelation therapy with EDTA is a treatment that is still available for intermittent claudication from private practitioners. There is no evidence that it has any benefit and good evidence that it is no better than an inactive substitute (placebo).

Do I need any other treatment?

The answer to this question for most people is no, but if your intermittent claudication symptoms are very severe, or if they do not improve, further treatment may be considered. Before considering any treatment it is important to obtain more detailed information on the arterial tree by using imaging techniques. This is because the type of interventions possible can only be decided after obtaining a road map of the arteries and then weighing up the risks of intervention against the benefits. An x-ray of the arteries (arteriogram or angiogram) or an ultrasound scan are usually performed first to provide more information about the disease in the arteries. Sometimes short blockages can be stretched open with a balloon (angioplasty) in the x-ray department. This is usually done under local anaesthetic and often involves an overnight stay in hospital. Longer blockages may be bypassed using a plastic tube or vein from the leg (bypass graft). This is a major operation under general anaesthetic and involves being in hospital for about a week to ten days. Very few people with claudication need this operation. In patients who develop critical limb ischaemia (the minority) some form of procedure to restore blood flow to the leg is essential to avoid amputation. The decision about surgery is usually one for you to make in discussion with your vascular specialist after they have explained the likelihood of success, and the risks involved.

Useful links

http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic862.htm

http://www.surgical-tutor.org.uk/default-home.htm?system/vascular/peripheral_vascular.htm~right

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/library5/health/clpl-00.asp

http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2001/march/Vowden/Doppler-assessment-and-ABPI.html – Very detailed explanation of Dopplers and ABI measurements

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000170.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peripheral_vascular_disease

Treatment

http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/159/17/2041

http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier

http://www.aafp.org/afp/20011215/1965.html

References

Leng GC, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG et al. Incidence, natural history and cardiovascular events in symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 1995; 25: 1172-81.

Kannel WB, McGee DI. Update on some epidemiological features of intermittent claudication. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985; 33: 13-18.

Widmer LK, Greensher A, Kannel WB. Occlusion of peripheral arteries – a study of 6400 working subjects. Circulation 1964; 30: 836-842.

Shearman CP. Management of intermittent claudication. Brit J Surg 2002; 89: 529-531.

Davies A. The practical management of claudication. Brit Med J 2000; 321: 911-912.

Burns P, Gough S, Bradbury AW. Management of peripheral arterial disease in primary care. Brit Med J 2003; 326: 584-588.

Stewart KJ, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG, Hirsch AT. Exercise training for claudication. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1941-1951.

Watson L, Ellis B, Leng GC. Exercise for intermittent claudication (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software, 2008.

Mazari FAK, Khan JA, Carradice D et al. Randomized clinical trial of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, supervised exercise and combined treatment for intermittent claudication due to femoropopliteal arterial disease. Brit J Surg 2012; 99: 39-48.

Strandness DE, Dalman RL, Panian S et al. Effect of cilostazol in patients with intermittent claudication: a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002; 36: 83-91.

De Backer T, Stichele RV, Lehert P, Van Bortel L. Naftidrofuryl for intermitent claudication: meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Brit Med J 2009; 338: b60 .

Robless P, Mikhailidis DP, Stansby G. Systematic review of antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of myocardial infarction, stroke or vascular death in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Brit J Surg 2001; 88: 787-800.

Caprie Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events. Lancet 1996; 348: 1329-39.

van Rij AM, Solomon C, Packer SG, Hopkins WG. Chelation therapy for intermittent claudication. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 1994;90:1194-1199.